|

| October 01, 2024 | Volume 20 Issue 37 |

Designfax weekly eMagazine

Archives

Partners

Manufacturing Center

Product Spotlight

Modern Applications News

Metalworking Ideas For

Today's Job Shops

Tooling and Production

Strategies for large

metalworking plants

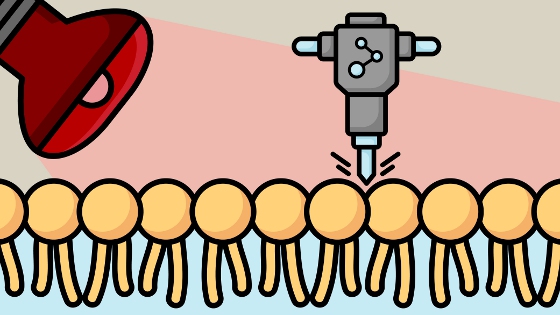

Powered by light, molecular jackhammers kill cancer cells with 99% efficiency

The first-of-its-kind technique could offer a much safer and more effective alternative to current cancer treatments. [Credit: Image by Rachel Barton/Texas A&M Engineering]

By Michelle Revels, Texas A&M University College of Engineering

Just as jackhammers can penetrate concrete, molecular jackhammers (MJH) are nanoscopic machines capable of creating blows so strong they can crack or rupture the cell membrane, decompensating and killing the cell. The MJHs are turned on by near-infrared (NIR) light that stimulates synchronized delocalized vibrations throughout the cell -- a mechanical action that can be exploited to rapidly kill cancer cells.

Researchers from Texas A&M University, Rice University, and the University of Texas-MD Anderson Cancer Center tested this method using lab cultures of human melanoma cells and mice with melanoma tumors. They found that the molecular jackhammers had a 99% efficiency in killing the cancer cells in vitro, and that 50% of the mice treated with this method became cancer-free. This development is the first of its kind and offers a much safer and more effective alternative to current cancer treatments.

This study was recently published in Nature Chemistry.

Stimulating vibronic modes in cell membranes works by activating aminocyanine molecules (the MJHs), which can easily adhere to the outside of cells due to their positive charge, opposite to the cell's phospholipid bilayer.

Once attached, MJH is activated by exposing these molecules to invisible infrared light (IR) frequency or energy, slightly lower than the energy of visible red light. Since red radiation has the lowest energy in the visible spectrum, any light below red is invisible, and this band or range of frequencies is called near-infrared (NIR).

When activated with NIR, electrons within the MJH create plasmons -- an excitation of the entire molecule that causes vibrations at an extremely fast rate. Driven by the NIR radiation, MJHs hit as if they were continually hammering the cell's surface. These collective hammer blows of the MJHs are strong enough to rupture or crack the cell's membrane, creating a decompensation sufficient to destroy it.

According to Dr. Jorge Seminario, professor in the Artie McFerrin Department of Chemical Engineering at Texas A&M University, one of the critical benefits of this theoretical approach is that it can predict, from first principles theory, how the MJH will behave in an experimental test. This previous knowledge is valuable, making the technique more cost- and time-effective while avoiding risky and expensive trial-and-error experiments.

Additionally, the likelihood of cancer cells developing a resistance to these molecular mechanical forces is extremely low, making these molecular jackhammers a safer alternative method for inducing cancer cell death.

"From the medical point of view, when this technique is available, it will be beneficial and less expensive than methods such as photothermal therapy, photodynamics, radio-radiation, and chemotherapy," said Seminario.

The researchers would like to continue testing and improving this technique so medical professionals can eventually utilize it to help treat cancer patients. The vast array of possible molecular structures paves the way for tailoring and using them to combat cancer.

"This is one of the very few theoretical-experimental approaches of this nature; usually, research in the fields related to medicine does not use first principles quantum-chemistry techniques like those used in the present work, despite the strong benefit of knowing what the electrons and nuclei of all atoms are doing in molecules or materials of interest," said Seminario.

Research collaborators include Dr. Diego Galvez-Aranda from the chemical engineering department at Texas A&M, Drs. Ciceron Ayala-Orozco and James M. Tour from Rice University, and Arnoldo Corona, Roberto Rangel, and Jeffrey N. Myers from UT-MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Published October 2024

Rate this article

View our terms of use and privacy policy